EMKP grantee Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran provides an overview of some of her recent work for the Paper people – making clothing from paper in Japan project.

In 2019 the EMKP supported my Paper people – making clothing from paper in Japan project. The aim of this project is to document how paper clothes are produced at two sites in Japan: Shiroishi (白石), a small town in Japan’s Miyagi Prefecture, and Tōdai-ji (東大寺), a Kegon Buddhist temple in Nara. The Japanese paper clothes central to this study are called kamiko (written as 紙衣 or 紙子), and are carefully handmade by fusing, stitching or folding together sheets of Japanese paper (washi 和紙). Across Japan, the practice is rare: only a few remaining communities of aging craftspeople are still making kamiko.

The project examines Japanese paper and paper clothing through historical and theoretical lenses, as well as through studio practice. I had the opportunity to work with kamiko, washi and takuhon-shi makers in Shiroishi, including: Mashiko Endō, a legendary Shiroishi local who, alongside her late husband Tadao revived and mastered the paper and paper garment making skills in the region in the postwar period; Fumiko Satō, who married into a paper-garment making family 50 years ago and has now herself mastered the takuhon-shi and kamiko-making techniques; Shinichi Kichimi, apprentice to his retired father, who are both takuhon-shi and kamiko makers; and the Kurafuto a group of locals who come together to keep local papermaking knowledge and practices active and alive, and who are cultivating raw materials from the same bulbs that have been in Shiroishi for hundreds of years. Local Shiroishi historians and archivists generously discussed objects they maintain in their collections and their local family histories related to paper and paper clothing. Outside of Shiroishi, my collaborators were in Tōdai-ji, in Nara, and included monks who were preparing to create and don paper robes to participate in an annual ritual, as well as monks who had previously participated.

A ceremonial robe made of Shiroishi washi, used at Tōdai-ji. Note the soot and bloodstains. Paper for this robe was made by Shiroishi local Mashiko Endō (Photo: Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran).

Papermaking in Japan

Paper may not seem like suitable material for making clothing but, if made in a specific way, it can become strong and durable enough to be used for clothing. For at least 1200 years, artisans across the Japanese archipelago have been making paper clothing using whole sheets of paper that have been softened for flexibility and treated with plant-based strengtheners. As early as 910 CE, Japanese Buddhist monks – the earliest custodians of papermaking knowledge in Japan – began creating garments out of their paper sutras, spawning a lasting tradition of wearing paper clothing that was later adopted by farmers and the upper classes. Through its history, paper has been worn for many reasons, including necessity, worship and aesthetic preference. Its widespread use peaked in the Edo Period (1603–1868) but it has now been replaced by other, less expensive, materials.

In the 17th century, the proliferation of tools and skills made washi accessible to all levels of society. It was used to disseminate images and texts, and incorporated in architecture, home furnishings, fashion and textiles. Hundreds of regional forms of washi, used to produce these unique items, were developed via small-scale operations, and each local derivation was contingent on a local climate, landscape and specific needs (Katakura 1988). The localized uses for paper flourished and vernacular applications developed as a replacement for more expensive materials such as leather, silk and cotton.

During the Edo Period, paper was used for doors, windows, crowns, hats, oilcloth, mats for sitting or sleeping, wax-cloth, faux-leather pouches, official certificates with watermarks, embossed wallpaper, lighting, raincoats, umbrellas, pillows, stationery boxes, serving trays, bowls, mosquito nets, small dishes, quivers, tea caddies, water receptacles, boxes, luggage and bags, lunch boxes, sandals, furniture, and tobacco pouches, among other things (Omura 1999).

Today, however, few communities in Japan continue to make paper, let alone paper clothing or textiles. For over 400 years, Shiroishi was synonymous with paper technology ranging from handmade paper, woven paper textiles, and paper clothing (Narita 1954). In Shiroishi, there are currently only four people who make the specially treated washi paper or the kamiko clothing as there is little consumer demand. The practices had been forgotten by the early 20th century and were re-learned during the interwar period by a group of Shiroishi locals who sought out knowledge from elderly people born in the Edo Period. This is happening again. The skills to make the raw material – Shiroishi Paper (Shiroishi washi 白石和紙) – are being revived by a group of passionate locals who are learning from these elderly revivalists. Kamiko is rarely made or used in Shiroishi, but locals hold on to the knowledge, tools and objects that are needed for making paper clothes.

Currently, a specific kind of white kamiko are made and worn by participants in the annual series of rituals held at Tōdai-ji, a Buddhist temple of great significance in Nara.

The O-mizutori Festival

During January and February 2020, I travelled to the Shiroishi region to document key materials, practices and stories related to kamiko. After many months of digital correspondence with a representative from Tōdai-ji, we agreed that it would be best to meet face to face and discuss the possibility of collaboration, the limitations of documentation and the implications of participating in this project. Ultimately, permission was granted to document the making of the paper robes and their use in holy rituals that take place annually in February and March and that culminate in a water-drawing festival commonly called O-mizutori. With the conditions of collaboration in place the plan was to return during the ritual festival, but then the borders closed and the return to Nara was complicated by COVID-19 travel bans.

Although it was not possible to complete the Tōdai-ji documentation this year, the O-mizutori festival is noteworthy as the only living tradition that connects the making and wearing of paper garments with an unbroken line of knowledge transfer in Japan’s kamiko-making communities. Monks participating in this festival are given paper, which they knead and prepare into a textile for the garment they will wear. Historically, they would have made the paper, and then construct this garment themselves, but in recent years outsourcing of papermaking and sewing skills is practiced. Observing the festival with collaborators at the temple is the only opportunity to learn about specific technologies and methods in kamiko creation, and the experience of its use. Hopefully it will be possible to return to Tōdai-ji in 2021.

Papermaking in Shiroishi

Shiroishi plays a central role in the history of washi and kamiko. Stories and records of the region’s papermaking prowess date back to the 17th Century. Even now, despite limited production and distribution, Shiroishi remains well-known for papermaking and kamiko. Handmade papermaking practices throughout Japan have been affected by large-scale mechanization, global warming, rural depopulation and increasing imports of material goods. This has decreased the demand for difficult-to-produce and relatively high-priced hand crafts like handmade paper. Paper is difficult to produce and generates a small return, therefore, in terms of its application in apparel production, it cannot compete with materials such as cotton, wool, linen, flax, and synthetics. In Shiroishi, some papermakers and paper finishers discouraged potential apprentices from taking up the craft, owing to the physical and financial difficulty it presented as a career.

Rather than apprenticing to become full-time producers or attempting to use papermaking as their sole source of income, the people producing paper in Shiroishi now do it in order to revive or prolong local traditions. Papermaking has taken on a culturally shifting symbolic value: it is no longer a real and necessary second job for farmers in the winter months, but it has become a second job (evenings and weekends) for passionate locals to enact and communicate the identity of the region.

Wallets and other items made from takuhon-shi at the studio of craftswoman Fumiko Satō (Photo: Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran)

In 2020, the practice of papermaking in Shiroishi is endangered, but a group of passionate locals are reconnecting with previously neglected skills by learning from members of an elderly group, who, in turn, between the 1930s and -40s, also came together to learn from elderly locals who had honed their papermaking and kamiko-making skills in the late 19th century. This older group created the conditions for a revival that lasted roughly one generation and made salient contributions to the long history of paper in the region. Their members mastered papermaking skills, travelled the country to research and collect paper objects and knowledge, and developed a frottage-like surface design technique to make sheets of embossed paper called takuhon-shi (拓本紙) that is not practiced anywhere else, which they used to make kamiko and other objects such as wallets and card cases. In Shiroishi, washi, takuhon-shi, and kamiko are thus entangled in history and practice.

Takuhon-shi craftswoman Fumiko Satō pointing towards a “pine-bamboo-plum” or shōchikubai (松竹梅) pattern. The pattern is indented into the paper using a variety of tools and materials (Photo: Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran)

The few original revivalist group members who continue to practice, as well as their middle-aged children or apprentices, generously offered their time to show me key materials and practices. Mostly they shared stories about changes to kamiko and washi production throughout the latter-half of the 20th century.

Mashiko Endō talking about a garment she constructed. Endō and her late husband Tadao were Shiroishi’s most prominent papermakers, until he passed away in the 1990s and she retired in 2017 at 93 years of age. She took no apprentice but generously shares her knowledge (Photo: Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran)

Raw Materials

As I was told many times, to make good kamiko, you need good paper, and to make good paper you need good fibers and tools. You also need time, and a willing family or community to aid in the many processing steps.

Paper is technically a nonwoven fabric that can be made from any combination of fibres. The three main tree fibres used to make washi in Japan are: kōzo, mitsumata and ganpi. Paper mulberry, or kōzo (楮 Broussonetia papyrifera), is the most widely used to make washi since ganpi (Diplomorpha sikokiana) cannot be cultivated and mitsumata (Edgeworthia chrysantha) has many small branches which make it laborious to work with. Kōzo’s long and narrow trunks, and rhizomatic structure allows for ease of cultivation, propagation, harvesting and, more importantly, processing.

This photograph was taken during a visit with Kurafuto members as they prepare the raw material for papermaking. After many steps, the yellow-white fibers from the inner bark of the Paper Mulberry tree are finally visible (Photo: Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran)

The paper required for good kamiko needs to be strong and light. The fibre distribution/density needs to be high enough and evenly distributed. Roughly 8-12 monme (匁) – a weight measurement used, among other things, for the weight of a sheet of washi – is suitable, with 12 being thicker than 8.

Contemporary and antique paper sword sheaths (katana–bukuro, 刀袋), collection of kamiko and takuhon-shi maker Fumiko Satō (Photo: Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran)

Making kamiko in Shiroishi

To make kamiko, first you need to knead and strengthen the crisp sheets of paper. This will soften them and give them more textile-like characteristics. Although the paper will be soft and lightweight, it remains durable. The construction and quality of the original sheet determines its strength, while the use of a starch adds a surface coating to the overall surface and the fibres themselves.

To strengthen and soften the paper, the sheets are treated with various liquids or pastes. The most commonly used is konnyaku (蒟蒻), which is starch made from the root of the Konjac plant (Amorphophallus konjac). Konnyaku can be used to keep the fibres on the surface of the paper from fluffing up and pilling, and also to make the clothes water-resistant. Other substances used include agar agar (kanten 寒天), fermented persimmon tannin (kakishibu 柿渋) or oils (including perilla, walnut, tung, linseed and poppyseed), which add anti-bacterial, water-resistant or strengthening properties to the paper. In all cases, the hand and surface texture of the paper feels different after the application of any of these materials. Historically, the resulting textiles were so strong that they could be laundered by hand, used as rainwear and for firefighters’ uniforms.

In addition to kamiko fabrics can be made from sheets of paper, sliced into strips, spun and then woven (shifu 紙布), collection of Kei Kawasaki, Kyoto (Photo: Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran)

Written records of the use of konnyaku – a common food product used as a jelly – as a finish for paper date back to 18th-century domestic handbooks (Omura 1999). Sheets with any combination of these materials applied are then kneaded by hand until they become soft and resemble conventional fabric. These sheets are then attached at the sides to form a bolt of cloth, which is cut and stitched together to construct a garment by using conventional hand or machine sewing methods and rice glue in some areas.

While the kamiko and its interrelated practices are hanging by a thread, a robust body of knowledge related to them exists, distributed across community members, archives and cities. I am very grateful to my collaborators and guides in this project who so generously offered their time and allowed their memories and experiences to be recorded. I look forward to continuing this research in the field and in the studio in order to collect and disseminate knowledge to a wider audience.

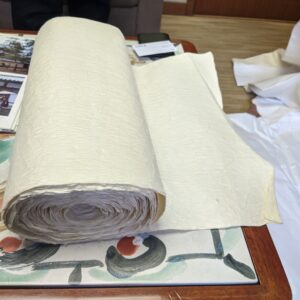

A bolt of paper cloth photographed at Tōdai-ji. Sheets for monk’s robes are a specific size, and in this image they have already been kneaded, treated, and attached, to create a bolt (Photo: Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran)

References

Katakura, Nobumitsu. 1988. Shiroishi Washi Shifu Kamiko. Tokyo: Keiyusha.

Mohajer va Pesaran, Daphne. 2018. “People and Placelessness: Paper Clothing in Japan.” Fashion Practice 10, no. 2 (June): 236–55.

Narita, Kiyofusa. 1954. A Life of Ts’ai Lung and Japanese Paper-Making. Tokyo: The Paper Museum.

Omura, Tomoko. 1999. “Konnyaku Paste and Kōzo.” The Journal for the Society for Washi Culture 7: 102–07.

Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran is a lecturer in the School of Fashion and Textiles at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia and the PI of the EMKP project Paper people – making clothing from paper in Japan