EMKP grantee Abidemi Babatunde Babalola and his colleagues provide an overview of some of their recent work for the Digitization of glass bead-making, use and meaning in Ile-Ife, Southwestern Nigeria project.

In this article we examine the process and significance of religious practices, broadly defined, in glass making and glassworking at Ile-Ife and Bida in Nigeria. Religious beliefs and rituals are central to human existence, and among the people of Nigeria – notwithstanding whether they follow a world or an indigenous religion – God/gods play a significant role in their daily affairs. Thus, in many African societies, crafts and other practices such as agriculture are connected to a spiritual patron. For example, among the Yoruba of southwest Nigeria, Ogun is referred to as a pathfinder and god/deity or patron in charge of metals. Again, among the Yoruba, farmers sacrifice to Orisa Oko (god of yield and harvest) for a good farming year.

The same is true also for glass and glass bead making in Ile-Ife, southwest Nigeria. In Ile-Ife, Olokun is regarded as the patron/goddess/deity in charge of glass and bead making. During our first visit to Ile-Ife for the EMKP project Digitization of glass bead-making, use and meaning in Ile-Ife, Southwestern Nigeria, our first contact was its Chief Falaju Olatunde – the Esinja Olokun Odua (priest of Olokun) – with whom we discussed the project and our plan for the rest of the season. Before delving into our discussion, Chief Falaju was swift to emphasize the significance of performing a sacrifice to Olokun. The propitiation, Chief Falaju explained, “is as essential as the project itself, so that we appease Olokun for the smooth running of the project and give all the interviewees sharp memory and revamp the skills of the demonstrators.” Sacrifice or, more broadly speaking, ritual and prayer are essential aspect of material practices at Ile-Ife.

Religion is equally crucial in glassmaking at Bida, another site where we are working as part of our EMKP project. In contrast to Ile-Ife, Bida is a predominantly Islamic city where indigenous religious practice is forbidden. Here, instead of performing indigenous or traditional rituals, the glass makers offered Islamic prayers to Allah for guidance, safety, and success in the making of bikini glass.

You may meet her goddess, Olokun

Olokun is a prominent female figure in Yoruba cosmology. She is both a historical patron and a deity associated with wealth, prosperity, and abundance. Her name has been linked to the Atlantic Ocean as the Atlantic is called Okun in the Yoruba language. Okun metaphorically represents endlessness and abundance. As a historical figure, Olokun is purported to have been the senior wife of Oduduwa, the paramount ruler of Ile-Ife (Oduduwa is also regarded as the progenitor of the Yoruba), in primordial time, but had difficulty bearing a child. However, Olokun was industrious and established the glass bead making industry. She was known for her elegance and beauty, and often adorned herself with colourful beads, which she also used to decorate her house. These attributes are featured in her eulogy: “Amolese bi alaari. Eso wumi lo, eba fono ile olokun han mi kin lo ko bi won ti n s’oge. Mowaje o, aje wami yeye oke oja” ([Olokun] whose feet are as clear as azure. I desire to adorn myself with accessories, would you show me the way to Olokun’s house to learn the practice. I sought wealth, and wealth seeks me, [Olokun] the mother of trade). Although it is unclear when and how Olokun was immortalized and then deified, shrines have been constructed in Ile-Ife as places for her veneration.

One such shrine was located at the famous archaeological site (Igbo Olokun), which is believed to have been Olokun’s workshop. Archaeological investigations at the site have reported numerous materials that strongly support the claim that the site was a glass and glass bead making industry. Another Olokun shrine is located at Wakunmoru compound. Moreover, there is a water spring (seleru) at Walode compound where Olokun devotees offer sacrifices and prayers to her. According to oral tradition, the Olokun visited and temporarily resided at Walode in her bid to seek help for childbearing. Because the shrine at Wakunmoru is the most active of these sites, we performed the sacrifice at this shrine.

Abidemi Babatunde Babalola with the Olokun priest Falaju Olatunde, other invited priests, and members of the community of Ile-Ife (Photo: Abidemi Babatunde Babalola)

The sacrifice

The regular annual festival dedicated to Olokun is usually held in August on a day determined by a priest. However, this priest has the authority to set occasional dates throughout the year to sacrifice to Olokun as long as he deems it fit for different purposes. The sacrifice was held on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019. Before this day, we arranged for all the necessary items needed for the ritual exercise. Votive items for Olokun include obi (kola nut), oyin (honey), iyo (salt), igbin (African giant snail – Acatina acatina), aadun (moulded fried maize powder with palm oil), eyele (pigeon), epo pupa (palm oil), oti (gin, preferably Seaman’s Schnapps) and a black she-goat. These items have symbolic meaning rooted in Yoruba cosmology. The sacrifice was held in the open. In addition to the Olokun priest, other invited chiefs/priests, the devotees, and the research crew, numerous bystanders and the entire local community assembled to witness the occasion.

Some of the items needed for the sacrifice (Photo: Abidemi Babatunde Babalola)

Chief Esinja Olokun started by offering the items at a shrine and said words of prayer for protection and success. He was assisted by another chief/priest who broke and threw the kola nut. The kola nut was thrown once, indicating good omen. Although the entire sacrifice was conducted openly, Chief Esinja Olokun later narrated that he went out to the shrine at dawn to offer prayers. He later received a sign that the prayer was accepted: “at 4.45 am, I went out to pray, and as soon as I got back in the house the rain started. I went there to say that these people are coming to offer sacrifice and implore the god to hear the prayers. The rain is a sign that the prayers were accepted. It is a form of reassurance of an answered prayer.” The sacrifice, which lasted for about 20 minutes, was followed by cooking. Since pounded yam is regarded as Olokun’s favourite it must be served on the day of the sacrifice, although it can be supplemented with other types of food. Primarily, the purpose of the sacrifice is to offer prayers to Olokun through the priest; but it is also a time of social cohesion, merriment, and feasting for the community.

An Obatala Priest wearing white beads (Photo: Abidemi Babatunde Babalola)

“The rain is a sign that the prayers were accepted. It is a form of reassurance of an answered prayer.”

(Chief Esinja Olokun)

Reverencing Olokun through beadmaking

The worship of Olokun does not end with elaborate sacrifices like the one convened by Chief Esinja Olokun. It is a continuous process that resonates with all the individuals connected with beads – from makers to sellers. For example, Mr Dipo Ogbogunleri, one of the project’s informants, demanded that a prayer be offered to Olokun before his demonstration could commence. Furthermore, sacrifices continue to be provided throughout the lifecycle of the production. Ms Elizabeth Oyinloye, Iyalode Kosere of Ile-Ife and a bead seller, talked to us about her early adulthood experience when her mother used to make glass beads. She stated that coins used to be given to children who passed by while glass production was ongoing. According to Elizabeth Oyinloye, this ritual exercise was a significant aspect of beadmaking that allowed the beads to come out well and beautiful with a clear and thorough perforation.

Chief Oyinloye further recounted her personal experience with Olokun’s benevolence: “I was a food vendor before I started selling beads. I incurred a lot of debt and had to stop the food business. The moment I picked up bead business, Olokun blessed and prospered me so much that I paid off my debt. I thank Olokun for this business and will continue to do it until I join my ancestors [die].” This encounter strengthened Oyinloye’s devotion and led her to construct a small portable shrine for Olokun in her shop. Oyinloye brings this shrine out daily to offer words of prayer to Olokun.

Praying and pouring of libation on a mobile Olokun shrine (Photo: Abidemi Babatunde Babalola)

Another bead worker we interviewed, Mr Alaba Owojori, who is also known as asindemade (maker of beaded crowns), also prayed to Olokun at the end of our interview while pouring a libation of schnapps.

The voices of these people show the centrality of rituals and other forms of religious belief in glass bead related activities in Ile-Ife with Olokun as the patron of the crafts in Yorubaland. The construction of a personal shrine by chief Oyinloye needs to be understood in terms of the dynamic nature of shrine making in Ile-Ife, the fluidity of their meaning, and the complexity of how researchers have classified, interpreted and engaged with their significance. Such dynamic practices remind us, as Insoll observes, that we need to recognize that the notion of ritual “is not a simple construct, a stable edifice of practice and custom” (2009, 293). Instead, the rituals at Ile-Ife should be considered as a form of mnemonic practice and, as showcased by chief Oyinloye, local practices can be understood within the framework of “shrine franchising,” whereby shrines are replicated elsewhere (Insoll 2006).

Praying to Allah: Religion, Masaga Glassmakers and Bikini Production

The abovementioned dynamics play out differently among the Masaga glass makers in Bida, central Nigeria. At the crossroad of west-central Nigeria, the Nupe city of Bida provides an ideal case study for investigating the production of raw glass by the Masaga glassmakers. Bida is situated on the Lanzu River, a tributary of the Niger River, and is located near the Benue and Kaduna Rivers. The Nupe city straddles the Savannah and Sahel regions, an area where movement and circulation of technology, commerce, and religion have taken place for centuries.

Masaga glassmakers are Muslim and are the custodians of glass production that has remained a secret formula for two centuries. The co-operative organisation is composed of hereditary guild members. This closed group maintains that its members descend from Egypt. Within this patrilineal society, the guild organisation maintains a specialised and monopolised glass production that follows Islamic practices and traditions.

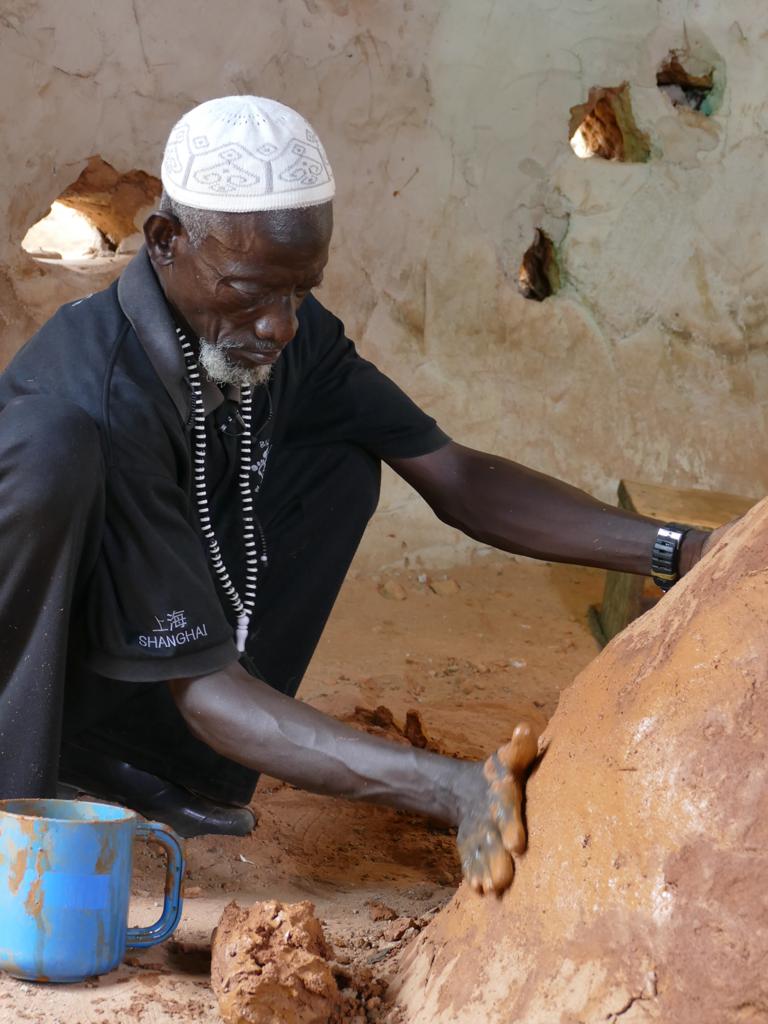

The glass marker Alhaji Abbas Umar wears Muslim prayer beads while constructing a furnace (Photo: Lesley Lababidi)

At the glassmaker’s workshop, the day begins with morning prayers and ends with the ṣalāt al-ʿaṣr, the late afternoon prayer. Greetings, gestures, observances according to Islamic traditions are integrated into every step of glass making.

At the glassmaker’s workshop, the day begins with morning prayers and ends with the ṣalāt al-ʿaṣr, the late afternoon prayer. Greetings, gestures, observances according to Islamic traditions are integrated into every step of glass making. Prayers come before and after each phase of glass production and are offered for the glory of Allah. Prayers ask for success and blessings. The local Imam is present at every guild meeting and guides the Masaga leaders with prayers. Before entering a glassmaker’s workshop or home, the Islamic greeting, as-salāmu ‘alaykum, is given. Prayers are said when gathering raw materials and constructing the glass melting furnace. The Imam blesses raw ingredients before dropping them into the furnace. During the process of annealing (a cooling process where the object is put in a bed of ash for a certain amount of time so that the glass object will harden uniformly), the Masaga glassmakers gather together for special prayers. When elders conclude that glass is successfully formed, cheers of gratitude, “Allāhu ’akbar,” rise from inside the workshop. As each piece of glass is retrieved from the furnace, the Imam, elders and glassmakers gather to offer prayers of thanks as they pass nuggets of molten glass from hand to hand.

The Masaga glassmakers of Bida are renowned for their production of glass beads and bracelets made from modern recycled glass and from locally manufactured raw glass known as bikini . Bikini is a black shiny molten glass that was used by Masaga craftspeople before the importation of modern glass bottles into this area. Bikini, classified as mineral soda-lime-silica glasses (Gratuze 2020), served as the main raw material for glass work between the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth centuries.

Concluding Remarks

From left to right Alhaji Mohammed Ndakolegbo, traditional head of Masaga glass community; Lesley Lababidi; Danladi Abubaker Masaga, secretary of Masaga Cooperative Society; and Alhaji Nma. (Photo: Lesley Lababidi)

Evidently religious beliefs are strongly linked to the material practice of glass/glass beadmaking at Ile-Ife and Bida. Elements of rituals and religious practices are observed by bead workers and sellers. Apparently, affiliation with any of the world religions, especially Christianity and Islam, does not prevent the devotees of Olokun at Ile-Ife from observing sacrificial practices to her goddess when necessary. The Yoruba characteristic of religious syncretism and tolerance must have served as the conduit through which such practice is embraced and preserved. Contrarily, this was not the case at Bida where only Allah is worshipped and Islamic practices take precedence in the crafting processes. In comparing the dedication of the glass industry to a primordial matriarch in Ile-Ife with Bida – where indigenous religious beliefs have no place in the crafting of glass and glass beads – one must also raise the question of whether the existence of such beliefs should be taken as an indication of the antiquity of a material practice in a particular area.

Bibliography

Bell, Catherine. 1992. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gratuze, Bernard. 2020. “Laboratory Analysis March, 2020.” Institut de Recherche sur les ArchéoMATériaux Centre Ernest-Babelon, UMR 5060 CNRS/Université d’Orléans.

Insoll, Timothy. 2006. “Shrine Franchising and the Neolithic in the British Isles: Some Observations based upon the Tallensi, Northern Ghana.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 16 (2): 223–28.

Insoll, Timothy. 2009. “Materializing performance and ritual: decoding the archaeology of movement in tallensi shrines in northern Ghana.” Material Religion 5 (3): 288–310.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Boluwaji David Ajayi (Research Assistant) and Ademola Adesiyan (Research Assistant) for their contribution to the project.