Cotton cultivation, textile production and dyeing have become completely industrialised and so cheap that traditional textile has become economically unviable. Today, only pockets of local cotton growers and weavers remains scattered throughout the globe and their numbers are diminishing as they age. Knowledge about the craft is also not transferred to the next generation, as options for employment are minimal and the youth are being pushed into other career possibilities. Nevertheless, where local production persists, cotton continues to be important for the local culture and traditions. Olivier Gosselain, Lucie Smolderen and Barpougouni Mardjoua from the project ‘From seeds to Rags’ are interviewed by EMKP volunteers Rosie Croysdale and Rachel Kader on the importance and challenges that textile making is experiencing in Dendi and Borgou of Northern Benin.

Rosie: Could you start by telling us a little bit about your project and its aims?

Olivier: Our project aims at documenting all facets of textile production and use in Northern Benin, in the historical regions of Dendi and Borgou. The aim is not only to collect information on the entire technical process, from cotton cultivation to the disposal of textile products (hence the title of the project!), but also to reveal the social, economic and religious dimensions of the textile sector, as well as tracing its transformations since the middle of the 20th century. This work extends the historical research we have been conducting in the area since 2011. We received the EMKP grant from the British Museum at a time when we felt the need to explore this key sector of the local history and finally respond to the demands of a generation of men and women faced with the rapid disappearance of an essential part of their lives. Our first fieldwork in February-March 2020 reinforced this conviction and confirmed the richness of the textile sector in Northern Benin, but also the danger of seeing whole sections of it disappear for good, after centuries of existence.

Rosie: Can you explain your decision to explore textile production in two target areas in North Benin, namely, Dendi and Borgou, and tell us more about what you anticipate will be different about cloth production in these two areas and why this might be important?

Lucie: Textiles have been of cultural, social and economic importance in both regions, but the sector has developed differently. In particular, production has practically died out in Dendi, while it has been transformed in Borgou. In the latter region, some workshops are nowadays semi-mechanized, to increase output. Weaving has also opened up to women, who work both on vertical mechanical looms and on artisanal or mechanical horizontal looms. Hand-woven fabrics are luxury products. In Dendi, the last representatives of the sector are elderly. There is only one male weaver still active in the village of Boïfo. Otherwise, a few old women still spin cotton “for memory” or for “those who need it.” This “need” is currently limited to the sphere of the cults of possession and the manufacture of amulets.

Olivier: Given these disparities in the persistence of weaving techniques, the work carried out in the two areas allows for better quality control of the data collected. For example, the direct observations made with active craftspeople from Borgou help to refine interpretation of the oral testimonies of craftspeople from Dendi who no longer engage in textile production. Direct observations make it possible to ask more precise and systematic questions to artisans who have sometimes given up working for decades. More prosaically, working in Borgou also allows us to confidently envisage the continuation of our EMKP research program notwithstanding the deteriorating security conditions in Dendi.

This district of the village of Karimama (Dendi) once had an important indigo dyeing workshop. Moudo Imorou, head of the district, shows the remains of vats in which the dyers used to soak the cotton fabrics. He has been fighting for several years for the site to be protected so that it can be shown “to the children of tomorrow”. (Photo: Olivier Gosselain)

Rachel: Why is this project important for Benin, have there been local demands to document the technical knowledge involved in textile production?

Mardjoua: Our project is of twofold importance. First, there are the people of the region, especially the holders of technical knowledge and skills, who are afraid of taking their knowledge with them to the grave and want it to be preserved in a form that can be passed on to the younger generations. This is why several informants expressed the wish to have a copy of the films made in the field (which is one of our final objectives). They shared their knowledge and showed their tools or gestures with enthusiasm, while at the same time expressing a certain bitterness for their own children’s lack of interest. Many concluded their testimonies with the words: “What I am delivering here is for the children of tomorrow.” Several also hope that our investigations will serve as a catalyst for some young people to take up crafts whose products are clearly valued in the West. The other important aspect is scientific. The in-depth study of the textile sector opens up interesting perspectives for those interested in the history of Northern Benin and the socio-economic organisation of the local populations. The documents collected in the field are also of interest to teachers, researchers, and students of the History and Archaeology Department of the University of Abomey-Calavi, in which a Teaching Unit dedicated to archaeology and material cultures has been created. The data on textiles will complement those previously collected on pottery, which until now have only covered the southern part of the country.

Lucie: While our project responds to strong local demand, it also reinforces certain individual initiatives for the preservation of technical heritage. Thus, we have frequently met women and men who conserve tools or materials associated with the textile industry “for the memory,” with the explicit ambition of being able to show them to the younger generations. Unsurprisingly, then, these people showed enormous enthusiasm and a willingness to teach us all their knowledge during field enquiries.

Rachel: Can you briefly outline the main stages in the production of cotton cloth?

Olivier: What we document corresponds to a craft sector and not a simple technical process. Indeed, textile production involves the interweaving of several processes which are carried out successively or in parallel by different actors. This explains the sociological and technical richness of textile production in northern Benin. It all starts with the cultivation of two basic raw materials: the cotton tree and the indigo tree. In the past, these plants were sown on small plots of land, sometimes alongside food crops. They are then harvested and processed by different actors. Women clean, card, and spin the cotton into threads of varying thickness and length. Men chop the indigo leaves, which are then chemically transformed by rotting. The resulting material can be packaged and stored. The cotton threads, sometimes previously dyed, are taken to the weavers who make narrow strips of fabric on horizontal looms and assemble them to make loincloths, shirts, trousers, or hats. If still blank, these items of clothing may then be taken to the dyers who dip them into vats filled with an indigo-based preparation. Finally, dyers often beat the dyed fabrics on wood to give them a shiny appearance.

Village of Niori, South Borgou. Adama Worou shows how cotton was carded in the past, using a bow and a wooden stick. This technique used in Dendi and Borgou was generally abandoned after the introduction of industrially manufactured cards. (Photo: Olivier Gosselain)

Rachel: In terms of division of labour, who is in charge of making the cloth? Is the labour divided in a specific way (i.e. gender, age)?

Olivier: In Dendi and Borgou—as in some other areas of West Africa—textile production is, to my knowledge, the only craft sector that transcends distinctions of gender, age, and socio-professional affiliations. Some operations are restricted to particular social segments, but taken as a whole, cloth production spreads literally across all strata of society. It is men who grow cotton. The harvest is intended for the women of their families and any surplus can be sold at the market. The women then take care of all the cotton processing operations leading to the production of threads. These threads are brought to male weavers who systematically belong to an endogamous servile class. Finally, men with no socio-professional background are in charge of dyeing the fabrics or possibly the cotton threads. The collaboration between age groups is particularly visible at this level: many dyers say that they have fully entered the trade when they were elderly, and no longer had the strength to work in the fields, yet they are assisted by young men in the more physical stages of the dyeing process. Thus, men and women, young and old, or people with or without servile status work together to produce cotton clothes. In this respect, cotton clothes embody the multiple dimensions of the social world within which they are produced and used.

Lucie: This organisational scheme corresponds to the situation that prevailed in the middle of the 20th century. In earlier times, it is more difficult to know exactly how things were done. The most striking aspect is that, despite this effective collaboration between genders, social classes or age groups, textiles are still a women’s story, and more precisely a story of married women. This may seem paradoxical, since it is men who are involved at the beginning and at the end of the production process: growing and harvesting cotton, weaving, and dyeing. In reality, as soon as the cotton is harvested, it is stored and managed by women. They are the ones who decide when to spin. They are the ones who gin the cotton and save the seeds for the following year. They make the threads and take them to the weaver, discuss with him what he is going to make, negotiate the price, and provide him with meals while the fabric is being made. It is they who supervise the sending of the loincloths to the dyers. And, finally, they are the ones who distribute the finished products to their family members.

Rosie: Are you looking to emphasise the social as well as the technical processes behind cloth production? Can you expand more on why this is important?

Olivier: Yes, of course! Like our previous research, our work for the EMKP falls within the field of cultural technology and therefore involves a data collection protocol designed to document the multiple dimensions of technical actions. These dimensions relate in particular to the relations between the persons involved—as the class or gender relations that we have just mentioned, but this extends also to the economic relations between producers and their customers—the relations to the ecological environment, the attitudes toward materials, transformation processes, and tools, the systems of thought, the religious beliefs, etc. These elements are fundamental. First of all, they allow us to contextualise technical actions and to understand how they fit into (and reinforce) the social system. Secondly, they help us to identify the logics behind technical choices (in terms of materials, tools, recipes, or devices) and to explain why certain parts of the technical sector are changing, disappearing, or still surviving today.

Lucie: Techniques are also a relevant avenue for exploring the history of a region. Approaching the past through techniques allows us to tell a different story from the one told by the elites, and also by men. As materializations of a lived or known past, techniques offer an alternative point of view, but also give a voice to categories of actors whose status means that they are often under-represented in oral history (such as members of endogamous socio-professional groups, descendants of slaves, women, and young people).

Village of Boïfo, Dendi. Goye Bani, the last remaining weaver of the area, uses a horizontal loom to make narrow strips of fabric which he will then assemble into a loincloth. Here, the cotton threads have already been dyed with indigo. (Photo: Olivier Gosselain).

Rosie: Collecting oral histories is an important part of your research with EMKP. can you explain how you begin an interview process and tell us something about your most interesting findings?

Olivier: In Dendi and northern Borgou, most of the February–March 2020 interviews were conducted with people we know well, some for years. They know why we visit them, and what we are looking for. They also trust us all the more because our work for the EMKP responds to their own request to preserve technical knowledge. All this makes things much easier; appointments can be made a few hours or days before the interviews and the latter do not require any special preparation. Nevertheless, interviews bring frequent surprises. One of the things we were not prepared for, for example, is the way in which the use of a camera affects the form and content of what our informants say. For example, after a few questions and answers, many of them suddenly start talking non-stop and freely, touching on subjects they had sometimes never mentioned before, which opens up new avenues of investigation for us. These moments were among the most exciting in the field. Another great satisfaction was the success of the part of our investigations dealing with disappeared techniques, which involves a combination of interviews, manipulation of old tools and various materials, photos and drawings. In most instances, we have literally seen technical actions relived before our eyes (and under the camera lens!), even if they had not been carried out for decades in some cases. The evocative power of gestures, words, and objects never ceases to amaze me!

Lucie: For me, one of the most interesting discoveries was when I interviewed a woman from Dendi, who is very involved in possession cults. She explained to us how the loincloth was intimately linked to the ganji (spirits of possession), since it was not only used to dress the possessed person during ceremonies, but also embodied the ganji within the household, outside ceremonial contexts. The spirit can be addressed by praying on the loincloth and “activating” it with certain substances, such as perfumes. I then understood why old loincloths were so carefully preserved and often perfumed and, more importantly, why they should not be considered as mere relics of the past, but powerful tools to act on the present.

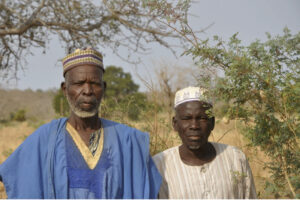

Village of Mamasi Gurma, Dendi. This photo was taken in 2013, during a visit to the field of Bwado Outeni (on the right-hand side of the photo). The latter had brought us there to show us an indigo tree that he kept as a witness of his former activity as a dyer. This moment left its mark on us, as did other situations in which individuals spontaneously engaged in a process of conserving their technical heritage. In February 2020, we found Bwado Ounteni again. No longer having the strength to work in the field, he had left it to his son to supervise. The latter had eliminated the indigo tree, much to Bwado Outeni’s dismay. After some research, we were nevertheless able to locate another one, which had spontaneously resown at the foot of a tree. This is where we conducted the interview. (Photo: Olivier Gosselain)

Rachel: With regards to the various dyes used and mentioned, what are the main ingredients used, and is there a symbolism surrounding the specific colours and choices?

Olivier: The most common colour used to dye fabrics in Dendi and Borgou is blue, which ranges from light to dark blue. As in many other parts of the world,[1] this blue colour is referred to as a “black colour”; the word “blue” does not exist in dendicine or baatonu languages. Most dyers derive this blue colour from the leaves of the Indigofera tinctoria, a small shrub cultivated for one to two seasons and from which one to two harvests a year could be obtained. The few Indigo plants that remain in the area today were sown spontaneously or were deliberately kept “for memory.” In the south-western part of Borgou, the dyers obtain the blue colour from the leaves of a wild climbing plant, the Philenoptera cyanescens (also called Lonchocarpus cyanenscens). Their preparation is much less complex than that of the Indigofera leaves, but the Philenoptera cannot survive in relatively dry areas such as Dendi or North Borgou. There is a much more marginal use of red, yellow, or greenish dyes obtained from the bark, roots, or leaves of other plant species. We still need to document these uses as well as the original raw materials.

Mardjoua: There exists a symbolism of colours in northern Benin, but this varies from one group to another. Nevertheless, there is a certain unanimity around the colour red, which is a sign of power and superiority. For example, during the annual gaani festival in Nikki, Banikoara, and the wider Borgou region, only the “crowned heads” have the privilege of wearing a red cap, or even a red outfit. Spiritually, the colour red is by far the preferred colour among cult leaders, such as the zima in Dendi or the siema in Borgou. There are also colours that embody consternation, mourning, and pain among the Baatombu or Gulmanceba. For the latter, for example, it is more appropriate to wear dark blue rather than white clothing during mortuary visits. In short, colour representations influence the choice of clothing to be made and worn. There are, however, “free” or “neutral” colours without any particular meaning. This is the case with yellow and light blue.

Rachel: Finally, what is the overall purpose of the cloth? It is used as an exchange item, for personal use or ritual use, or a combination of the above?

Lucie: In the past, textiles were used to dress all members of the family. Clothing was a marker of social status. The notables or the chief, for example, were more likely to wear Hausa-influenced clothing, typically associated with the Muslim world (large, shiny, dark blue boubous dyed with indigo). Women wore locally dyed textiles. Their loincloths could be either plain blue or an alternation of white and blue stripes. Common men favoured white loincloths. However, textiles did not only have a clothing function; they also intervened in the sphere of matrimonial exchanges. The mother of the bride offered two loincloths to the newlyweds—one to decorate the bridal chamber, the second for the husband. This trend became the rule in the 1950s and 1960s, under the influence of the Zarma of Niger. A new style of loincloths with geometric decorations, coming from the north, was particularly appreciated in that regard.

Clothing also intervenes in the ritual sphere. It is intimately connected to the ganji, the spirits of possession. On the one hand, the loincloth is the garment used to dress the person possessed by a particular spirit during a possession ceremony; on the other hand, it embodies the ganji outside possession contexts. This loincloth must be taken care of and repaired if it is damaged. One can pray on it to address the ganji in everyday life. It acts as a mediator between the visible and invisible world (in the same way as a mask for example). Fragments of cloth strips are also used to make charms, whether these are made by an animist priest or a marabout. As a material, cotton is charged with magical efficiency. Nowadays, these practices tend to disappear under the influence of the new preachers close to the Isala movement (an Islamic trend coming from Nigeria and Niger). They prohibit all “maraboutic” practices and anything related to the past in general, which increases the threats to the old textile sector.

[1] See the amazing book of Michel Pastoureau: Blue. The story of a color (2001, Princeton University Press).