The borderland between Sudan and Ethiopia is home to a variety of ethnic minorities that have found in its challenging geography a refuge against their powerful neighbours. Despite slave raids, invasions and war, the borderland peoples have managed to preserve their cultural identity and escape effective state control until the early twenty-first century. This explains why some of these groups have remained unknown outside the region—overlooked by anthropologists and state bureaucracy alike. The whereabouts, traditions, material cultures and language of some of these communities have only been determined during the last few years and some are still to be documented. The EMKP project Ethnic minorities and threatened materialities in Western Ethiopia intends to record the material assemblages of some of the least known groups of the Ethiopian-Sudanese borderland. Here we present some of the communities we work with, our objectives and methodologies, the research undertaken so far, and then describe what one category of objects—artefacts used for making beer—can tell us about a people and their history.

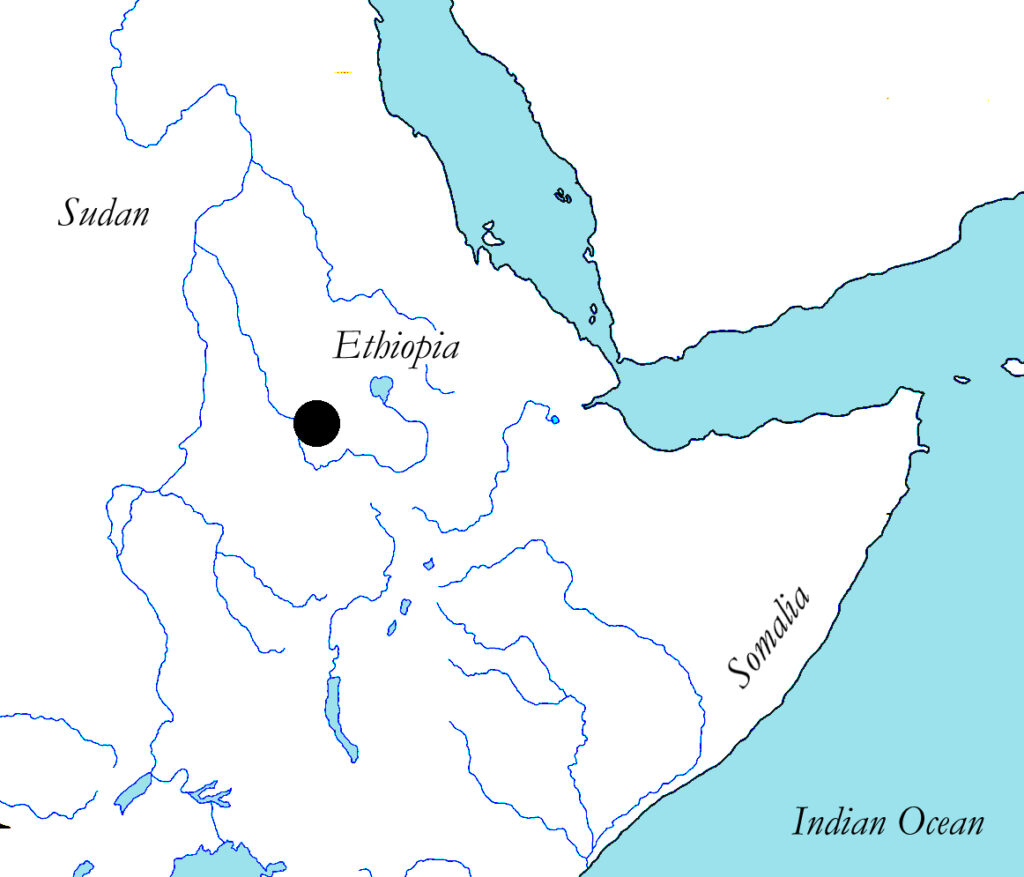

Figure 1. Map of the Horn of Africa with the location of the Hamaj people (black dot).

We conducted our first field season in the area north of the Blue Nile during January and February 2020 (Figure 1). We worked with groups known historically under the generic name of Hamaj. Their cultural specificity has been unclear for a very long time and the term has been regarded as an external denomination concealing a diversity of groups (like “Indian” or “Kafir”). Our research has shown that the Hamaj are indeed a diversity of groups, of whose existence we knew very little or nothing, but also that these groups are strongly related and share similar languages, cultures and material cultures.

Hamaj materialities

The distinctiveness of the Hamaj has been blurred in the Sudan during the last decades, due to the influence of Islam and the spread of Arabic and a Sudanese identity. It is in Ethiopia where peoples known as Hamaj have preserved their culture more vigorously (Hernando et al. 2019). In this case, the problem is that they have been lumped together with the neighbouring Gumuz, with whom they are related: they speak languages that derive from the same ancestors, called Bega by linguists, and their cultures are similar in various ways.

At the same time, their differences are remarkable and Gumuz and Hamaj do not consider themselves to be part of the same collective. In fact, the Hamaj in Ethiopia do not see themselves as part of one group, but rather as distinct communities, of which we have been able to document three: the Dats’in, the Abu Ramla and the Kadalu. References existed only for the latter, who were first mentioned by Dutch traveller Juan Maria Schuver in 1881 (Schuver 1996). During our 2020 field season we set out to document the material assemblages of the Abu Ramla and Kadalu (the Dats’in we had already studied, see Hernando et al. 2019), as well as of a third group, the Banea, whose identity as Gumuz or Hamaj was unclear to us.

Material culture turned out to be crucial to distinguish between Hamaj and Gumuz and, in fact, the production and use of material culture is essential to the making of distinct Hamaj identities. Unfortunately, its existence is threatened by the advance of industrial consumer goods, globalization and the establishment amid them of settlers from highland Ethiopia, who bring their own customs and material assemblages. The material culture of the Dats’in, Abu Ramla and Kadalu tells us about their unique beliefs, their customs, their history and their relations with other communities in the borderland. It is for this reason that we decided that it was more pressing to document entire material assemblages than just a single category of artefacts. Our approach is further justified by the fact that we know virtually nothing of the Hamaj. It is necessary to record the artefacts they make and use before they disappear or are drastically changed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Plastic containers are rapidly replacing pots and gourds among the Hamaj peoples.

Much of the traditional material culture of the Hamaj of Ethiopia is still preserved: vernacular architecture (including houses, granaries and goat houses), basketry, furniture, pottery, agricultural tools, spears, throwing sticks and bodily adornment. Yet industrial artefacts are becoming increasingly popular: plastic and metal containers are quickly replacing pottery and gourds, while their disposal creates environmental problems. Access to mass-produced items is easier these days because new roads have been opened and inexpensive motorbikes are now available to make trips between remote villages and towns. The impact of industrial goods can be seen in the decrease of locally-produced artefacts, but also in the reduction of typological diversity: people have fewer and less varied pots than even a decade ago—a phenomenon that is common throughout Ethiopia. Vernacular architecture, while more resistant to change, is also experiencing transformations: among the Kadalu, for instance, square houses made of daub (galus), typical of Sudan, are now replacing local round houses made of perishable materials.

Techniques for documenting a material world

In our work, we combine new and old techniques to achieve the most accurate and complete recording of Hamaj materialities—a sort of material thick description. The use of multiple media is, in fact, common in archaeological practice, so what we intend to do is to apply such a methodology to living, ethnographic contexts. Therefore, we use a drone to map villages (Figure 3), digital photogrammetry to record granaries and houses (both indoors and outdoors) (Figure 4), and traditional hand-drawn maps to document activity areas. We make inventories of each and every artefact present in a home and relate the inventories to detailed maps of the domestic structures (Figure 5). Space is crucial for understanding the material world: every artefact, technological process and social activity has a spatial dimension to which objects and bodies are inextricably linked. We also take photos of objects in use and in situ (for example, beer pots inside the house or a woman making a necklace), but also in isolation and with a neutral background, so that the details, textures and unique character of each artefact are captured with precision (Figure 6). The details are further registered through technical drawings that allow us to interpret the pieces and emphasize aspects that are perhaps not obvious in the photographs (Figure 7). In addition, chaînes operatoires (from basket making to a healing ritual) are recorded in video (Video 1). We understand material assemblages holistically and our documentation intends to be equally holistic.

Figure 3. Amzibil, a village of the Abu Ramla people, who take their name from the volcanic mountain in the background.

The recording of material culture is accompanied by interviews with the people that make and use the artefacts, women and men, old and young. To make sense of things it is important to understand the wider cultural background in which they are produced and employed, so our questions and observations are not limited to technological processes, but to the social context in which they are deployed—commensality or healing rituals, for instance—spiritual beliefs, and historical consciousness.

A core object: the Hamaj beer jar

While we record all traditional, locally-made objects, not all of them have the same importance among the Hamaj. As in all societies, only a few artefacts are so important that can be considered “core objects”, a term coined by cultural psychologist Ernst Boesch (1991) and referring to those artefacts that, for their social and ritual uses, are vital for the self-definition of a culture. Basket-weaving, for instance, is relevant not so much because of its outstanding cultural role, but because it is sold in markets and provides extra revenue to homesteads. They will probably last longer than other artefacts that have specialized functions and do not circulate outside the group, such as elaborate hunting spears. If we have to choose an object that is important for cultural, ritual and social reasons, it is the beer jar (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Bätalu Ahmed, an Abu Ramla potter, makes a pot while Worku Derara takes notes.

Traditional beer is still made in many parts of the Horn of Africa, but amphoroid beer jars, as those used by the Hamaj, are produced and employed only in certain areas. In fact, we have only documented them among three groups that are spatially contiguous—the Hamaj themselves, the Bertha and the Gwama—and, in the case of Bertha and Hamaj, historically linked and at times confused. The pots are very similar in the three cases. Spatial contiguity and morphological similarity mean that beer jars have, in all likelihood, a common origin. This origin can actually be traced: very similar beer jars are first attested in Meroitic sites in Nubia (northern Sudan) two and a half millennia ago and they appear in the archaeological record ever since. The formal similarity is striking and so are the social uses of the alcoholic drink. Beer jars appear as grave goods in Meroitic and post-Meroitic cemeteries and sorghum beer was used in ritual contexts. Likewise, sorghum beer, with a very low alcohol content, is still consumed at funerary ceremonies among the Hamaj, during which many jars are brought together to cater for extended families, friends and neighbours coming to the funeral. It is also consumed on many other social occasions, such as weddings and work parties (Figure 9). Making beer for neighbours and consuming beer collectively reinforces social ties within the community. It is a way of utilising the surplus of cereals and therefore preventing the emergence of social inequalities. Beer is also offered to Qumsinjil, a spirit who lives in the back of the house, where beer is brewed and stored. Beer, then, feeds the living, the dead and the spirits.

Figure 9. Decorated beer pots, ready to be used in communal consumption, inside an Abu Ramla home.

The jar—which, curiously enough, is called jar in the Abu Ramla language, and jara in Dats’in—is more than a container for the liquid. The fact that it has barely changed in millennia is proof of the relevance and importance of the contents and the container. Another proof of its importance is that, in a material world largely devoid of ornamentation, beer jars are beautifully decorated—usually the only pots to receive any ornamental treatment. It is an object that distinguishes the Hamaj from neighbouring groups, who use large open vessels, instead of amphoroid jars, to prepare and serve the drink. Such a distinctive character is extended to other objects related to beer production, such as the filter made of vegetable fibres (diŋ). The Hamaj diŋ is almost identical to the Bertha, but very different from the neighbouring Gumuz, a fact which again relates Hamaj beer to a shared and ancient Sudanese tradition.

The jar is a contemporary artefact, but also a historical one that confirms the history transmitted by both written sources and the Hamaj, and that situates their origin in central Sudan during the Middle Ages. The possibly eventual disappearance of the pot in which the Hamaj brew and store beer will mean the interruption of a venerable tradition. The pressure of Islamization, global modernity and new consumption and social practices may put an end to sorghum beer making, collective beer drinking, and the making of jars and filters. A whole social, ritual and material world will vanish. But at least, this world will be recorded for the future.

References

- Boesch, E. (1991). Symbolic action theory and cultural psychology. New York: Springer.

- Hernando, A., González-Ruibal, A., & Derara-Megenassa, W. (2019). The Dats’ in: historical experience and cultural identity of an undocumented indigenous group of the Sudanese-Ethiopian borderland. Journal of Eastern African Studies 13(3): 504-524.

- Schuver, J. M. (1996). Juan Maria Schuver’s travels in north east Africa 1880-1883. Translated and edited by W. James, G. Bauman and D. H. Johnson. London: The Hakluyt Society.